This Spotlight highlights the ways in which DRK-12 projects are engaging families and caregivers to support STEM learning, including building parent leadership capacity and co-creating and testing home-based activities, and why this engagement has been important to their work. The nine featured projects discuss the impacts and benefits of family engagement, offer advice on successful approaches to family engagement, and share insights and findings. In our featured blog post, Cory Buxton and Diana Crespo Camacho discuss the need for more research in the area of family engagement to support STEM learning.

This Spotlight highlights the ways in which DRK-12 projects are engaging families and caregivers to support STEM learning, including building parent leadership capacity and co-creating and testing home-based activities, and why this engagement has been important to their work. The nine featured projects discuss the impacts and benefits of family engagement, offer advice on successful approaches to family engagement, and share insights and findings. In our featured blog post, Cory Buxton and Diana Crespo Camacho discuss the need for more research in the area of family engagement to support STEM learning.

- The Role of Family Engagement in Promoting STE(A)M Learning | Blog post by Cory Buxton and Diana Crespo Camacho

- Featured Projects

- CAREER: Black and Latinx Parents Leading Reform and Advancing Racial Justice in Elementary Mathematics (PI: Frances Harper)

- CAREER: Fostering Early STEM Exploration with Gifted and High Ability Black Girls and Their Elementary Teachers Through Culturally Relevant Experiential Learning Activities (PI: Brittany Anderson)

- Co-developing a Community-based Science Education Curriculum Framework for Disaster Justice and Resilience: A Response to the 2022 Buffalo Blizzard (PI: Noemi Waight)

- Developing an Early Mathematics Intervention for Children with Disabilities in the Home Learning Environment (PI: Gena Nelson)

- Integrating Science with Mathematics and Engineering: Linking Home and School Learning for All Young Learners (PI: Ximena Dominguez)

- Parents, Teachers, and Multilingual Children Collaborating on Mathematics Together (PIs: Marta Civil, Rachel Pinnow, Beatriz Quintos Alonso)

- Supporting Students' Language, Knowledge, and Culture Through Science (PI: Cory Buxton)

- The Smart Playground: Computational Thinking Through Robotics in Early Childhood (PIs: Marina Bers, Andres Bustamante, Chris Rogers)

- Young Mathematicians: Expanding an Innovative and Promising Model Across Learning Environments to Promote Preschoolers' Mathematics Knowledge (PI: Jessica Young)

- Additional Projects

- Related Resources

Blog | The Role of Family Engagement in Promoting STE(A)M Learning

Cory Buxton, Professor of Science Education, and Diana Crespo Camacho, Ph.D. candidate, Oregon State University

In this blog post, we briefly reflect on how family engagement in STEM learning has evolved as a research topic from the start of the NGSS era to the present day.

In this blog post, we briefly reflect on how family engagement in STEM learning has evolved as a research topic from the start of the NGSS era to the present day.

Ask nearly any teacher or school administrator, and they will tell you that family engagement is important to the success of their school. Ask them about family engagement in STEM subjects specifically, and you are likely to hear examples of how STEM fairs and events are some of the school's most engaging and well attended events. Press a bit more, however, on the specific family engagement goals, the specific activities for meeting those goals, and the alignment between those activities and goals, and you will often encounter a good deal of uncertainty. We believe that the reason for this uncertainty is, at least in part, that while family STEM engagement activities are fairly common, their systematic study and dissemination of promising practices are rare...Read more.

Featured Projects

CAREER: Black and Latinx Parents Leading Reform and Advancing Racial Justice in Elementary Mathematics

PI: Frances Harper

STEM Disciplines: Mathematics

Grade Levels: PreK-5

Project Description: CAREER: Black and Latinx Parents Leading chANge & Advancing Racial Justice in Elementary Mathematics explores possibilities for localized change led by parents. By making explicit how to foster and increase parents’ engagement in solidarity with community organizations and teachers, this project provides a model for other communities and schools seeking to advance racial justice in mathematics. Through critical community-engaged scholarship and in collaboration with ten Black and Latina moms, their families, and three community organizations, PI Harper co-designed an educational program aimed at building parents’ capacity to catalyze change in mathematics education within local communities. In 2022-23, the educational program focused on developing a shared vision for racial justice in elementary mathematics. This year (2023-24), mothers built their capacity as leaders by designing and carrying out their own participatory action research projects to advance racial justice in mathematics within their local spheres of influence. These five projects focused on preparing Latinx children and families to navigate high-stakes testing in mathematics, holding schools and teachers accountable for the mathematics learning of neurodivergent Black and Latinx children, exploring rhythmic learning in mathematics for Black children, advocating for state policy changes to in-state tuition eligibility based on mathematical decision-making, and raising awareness of racial injustice in mathematics among other parents and caregivers. In 2024-25, we will launch a second educational program, led by parent leaders, for teacher professional development that supports elementary teachers to learn with and from families as partners for advancing racial justice in mathematics.

What advice would you give to other projects that are considering a family engagement component to their work?: Do not underestimate the time necessary for relationship development and trust building across different partners (e.g., university, community organizations) and among parents. Initially, my plan was to focus both on establishing a shared vision for racial justice in mathematics and building parents’ capacity for leadership in the first year of the educational program. However, I found that parents needed additional time to deeply understand and connect around a vision for racial justice in elementary mathematics. Especially as I brought together different partners from the university, community organizations, and families, from both Black and Latinx communities, building trust took considerable time. That trust was necessary before mothers felt comfortable being vulnerable within the group and before we could start to disrupt power dynamics that positioned university partners and community organization partners as more expert in mathematics and in education than the parents themselves. I found that we needed a full year of working together before there was a sense of community and solidarity among group members. For that reason, I decided to delay introducing teachers to the group for another year to focus on building parents’ leadership capacity in the second year of the educational program.

What challenges have you experienced related to family recruitment and engagement and what strategies have you identified to address them?: I experience an ongoing tension between mothers’ sense of urgency in helping their own children to succeed in school mathematics (despite injustices) and long-term plans for change in school mathematics for collective benefit and towards justice. For example, these two goals have come into conflict around high-stakes standardized testing. Mothers are naturally invested in helping their children succeed on such tests, especially in a context where doing so is tied to grade-level advancement. We currently offer children opportunities for play-based enrichment in STEM while the mothers are meeting with community and university partners, but mothers increasingly asked us to use that time to focus on test preparation. My goals of offering a space for children to play and explore with mathematics conflicted with the mothers’ priority of preparing their children for state testing. A strategy for approaching such tensions is to listen to and respect the parents’ priorities for their children, while also encouraging them to critique whose interests are served by such school-based requirements. In this case, two of the mothers decided to focus on test preparation as part of their participatory action research project; they used funds set aside to support their research to offer tutor for their children and other children in their communities. Thus, we continued to offer play-based exploration for children during meetings. At the same time, I also created opportunities for the whole group to explore standardized testing in mathematics as a racial justice issue during our meetings. This has allowed us to see the bigger picture together, while meeting the immediate needs of families.

Initial Findings: This project uses a mixed methods research design by pairing narrative inquiry and social network analysis. Primary research questions are longitudinal in nature, asking: (1) What are the lived experiences of Black and Latinx parents as they build capacity to lead change in elementary mathematics; and (2) How does a vision for racial justice in mathematics develop among the group and extend beyond the group? Preliminary findings of parents’ lived experiences and how the vision for racial justice has spread among social networks are expected by the end of 2024.

Products: https://francesharper.com/planar/ - This is an educator facing website. A revision with additional materials and resources is planned for summer 2024. Parents are expected to present the findings from their participatory action research projects at upcoming conferences this summer and fall. Details of those presentations will be shared on the website.

CAREER: Fostering Early STEM Exploration with Gifted and High Ability Black Girls and Their Elementary Teachers Through Culturally Relevant Experiential Learning Activities

PI: Brittany Anderson

STEM Disciplines: Early exploration of STEM broadly with elementary students. There are units on Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math

Grade Levels: K-5

Project Description: CAREER: Critical and Culturally Relevant Experiential Learning: Fostering Early STEM Exploration with Gifted and High-Ability Black Girls and their Elementary Teachers develops community-engaged educational programs that center STEM education pipelines and pathways for high-ability and Gifted Black Girls (GBGs). The central aim of this project is to generate an actionable theory of change for elementary GBGs to foster a sense of belonging in STEM, early STEM exploration and development, and nurturing a STEM identity, through Critical and Culturally Relevant Experiential Learning (CCREL). The project uses a university-school-community (USC) partnership model to co-design programming, and co-create sustainable strategies and practices to identify and develop talent of GBGs in elementary schools, with teachers and families. The first educational program—See Me in STEM (SMIS)—focuses on community-based learning and CCREL practices and exploration, which, in turn, expands the STEM capacity of Black girls and their families, in partnership with teachers, to engage in STEM learning and doing using home-life connections. The second educational program—Teachers as Talent Catalysts (TATC)—provides elementary teachers with the professional learning to interrogate their STEM pedagogical practices in collaboration with families, messages about Black girlhood and talent development, and ways to integrate CCREL STEM teaching processes in their classrooms. The project’s goal is to illuminate the historical legacies of STEM in Black communities, spotlighting the everyday practices of STEM in Black homes using problem-based learning. Everyday STEM engagement includes cosmetic science (hair, make-up), culinary science, outdoor exploration, engineering and technology design challenges with robotics, coding, and gaming, and community-based mathematical experiences.

What impacts or benefits are you seeing related to family engagement?: Family engagement was central to development and now implementation of both the TATC and SMIS programs. I approach family engagement through (re)membering—using my own memory work of learning and doing STEM— and identifying the STEM activities used frequently by and with my grandmothers. The programs actively disrupt what has been traditionally considered STEM, and centers community-based STEM praxis to engage the girls, their families, and teachers.

What impacts or benefits are you seeing related to family engagement?: Family engagement was central to development and now implementation of both the TATC and SMIS programs. I approach family engagement through (re)membering—using my own memory work of learning and doing STEM— and identifying the STEM activities used frequently by and with my grandmothers. The programs actively disrupt what has been traditionally considered STEM, and centers community-based STEM praxis to engage the girls, their families, and teachers.

Disrupting this narrow view of STEM has been beneficial to all, restructuring the perception of who does STEM (identity), and how it should be done (praxis). The caregivers and teachers have been able to identify and discuss their conceptions of sustainable home-school connections, in conjunction with the needs and interests of Black girls. Outside of emails and family-teacher conferences, families and educators rarely had meaningful interactions. Through these programs, they have been able to co-construct multi-generational knowledge, establish creative ways to approach learning for the girls, and simultaneously disrupt messages about Black girlhood and womanhood. An active component of the program is tethered to “keeping the learning going,” and the girls, their families, and teachers have ongoing activities they complete during programming and in their homes. The teachers have been able to identify their own STEM identity development and practice, and observe how the girls engage in problem-based learning. Similarly, the families have enjoyed the co-creation of activities and the opportunity to determine the STEM interests of the girls. Though the project is early in its implementation, participants have described the space as being safe and healing.

What advice would you give to other projects that are considering a family engagement component to their work?: Meaningful family engagement requires researchers to consider the interactive, dynamic, and possibly complicated ways to co-develop and co-construct knowledge and processes in partnership with families. These considerations need to be formalized both in the grant proposal and in the delivery of proposed integration. As a PI, I have to create space in the programming and research plans for the families to identify, connect, and make sense of the work. To do this, it is not always the easiest or most comfortable pathway for me or the extended research team- it can be a messy process.

What advice would you give to other projects that are considering a family engagement component to their work?: Meaningful family engagement requires researchers to consider the interactive, dynamic, and possibly complicated ways to co-develop and co-construct knowledge and processes in partnership with families. These considerations need to be formalized both in the grant proposal and in the delivery of proposed integration. As a PI, I have to create space in the programming and research plans for the families to identify, connect, and make sense of the work. To do this, it is not always the easiest or most comfortable pathway for me or the extended research team- it can be a messy process.

As more scholars engage in scholarship to construct new knowledge and high-leverage pedagogical practices that involve families, intentionality is key. To integrate the nuances through an intersectional lens, the critical reflections and implementation of the project, we should account for the time, knowledge, and labor (visible and invisible) of families into their budgets, project scope, and dissemination. The families cannot be considered supplementary to the project, but critical to the development of the programming and practices. This project positions the caregiver(s) as equal partners, because their funds of knowledge are invaluable to the professional learning of the teachers and function of the SMIS program. The caregivers are also essential to the evaluation and implementation of the project. Caregivers will have their own sessions where we collaboratively discuss strategies and practices (i.e., academic, social-emotional, expectations), advocacy, and tenets that need to be integrated into both programs.

Products:

- Anderson, B. N. & Littlejohn, G. S. (in-press). “Oh, that’s engineering?”: Complicating Black women educators understanding of engineering practices in urban elementary schools. Special Issue: Provocations -Journal of Pre-College Engineering Education Research (J-PEER).

- Brown, T. T., Anderson, B. N., & Wigfall, K. (2024). “Am I no longer gifted?”: Imagining a more capacious world for Black girls in alternative education. Black Educology Mixtape Journal, 2(1). Retrieved from https://repository.usfca.edu/be/vol2/iss1/3

- Dolet, T., & Anderson, B. (2023). SEE ME in STEM: Exploring out-of-school STEM education for gifted Black girls. Teaching for High Potential, 1, 16–18. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2897288811?pqorigsite=gscholar&fromope…

- Anderson, B. N., Coleman-King, C., Wallace, K., & Harper, F. K. (2022). Advancing critical and culturally relevant experiential learning: Preparing future educators in collaboration with cooperating teachers to support STEM engagement in urban schools. The Urban Review, 54(5), 649-673.

Co-developing a Community-based Science Education Curriculum Framework for Disaster Justice and Resilience: A Response to the 2022 Buffalo Blizzard

PI: Noemi Waight

STEM Disciplines: Earth Science and Environmental Science

Grade Levels: K-12

Project Description: In the immediate aftermath of the 2022 Buffalo blizzard (Buffalo, NY), this RAPID project responds to this disaster by co-developing a community-based science education curriculum framework focused on disaster justice and resilience. We have documented the experiences, reflections, and needs of the Buffalo community after the disaster, which will be instrumental to address the human and social aspects of disasters in a more holistic manner in the context of science education. This project highlights the criticality and temporality of documenting the experiences of urban science teachers, Black and Brown community leaders, and families who were directly, and disproportionately, impacted by the Buffalo blizzard. Specifically, this disaster justice and resilience project reflects temporal urgency, the immediacy of the 2022 Buffalo blizzard provides a critical window to: (a) document via individual semi-structured interviews, science teachers’, community leaders’, and families’ experiences and reflections of the 2022 Buffalo blizzard as it relates to weather and climate curriculum and instructional approaches and needs; community approaches to preparedness and needs, family needs, school support, and resources; cultural and racial impact of climate-related disasters (in terms of loss of life and geographical impact); and justice/injustice, resilience, and emotions. In addition, families alongside other community members and teachers, and science teachers comprise a coalition—people who were directly impacted by the 2022 Buffalo blizzard—that will engage discussion of the main findings and big ideas identified from the first phase of semi-structured interviews. The coalition’s contributions will inform the co-development of a set of guidelines for a science education curriculum framework for disaster justice and resilience for in and out of school use.

The inclusion of families in Black and Brown communities most impacted by the 2022 Buffalo blizzard—parents, children, and siblings—reflect a critical community voice and advocacy in the movement to transform disaster preparedness practices within and out of school.

What impacts or benefits are you seeing related to family engagement?: The impact of family engagement is significant and critical to this project. Families in Black and Brown communities represent a significant experience and voice in understanding the impact of, knowledge, and practices in disaster justice and resilience. What is more, families offer a collective perspective, a cohesive village orientation that is responsive to the experiences, needs, and well-being of children, adults, and the extended community. Families in this study were also closely involved in community-engaged work and thus understanding these multiple roles was foundational. The preparedness of families underscored the core of communities before, during, and after the 2022 Buffalo blizzard.

What challenges have you experienced related to family recruitment and engagement and what strategies have you identified to address them?: As part of this study, the most significant challenge was flexibility with time given family’s activities (school and familial). To mitigate this challenge, the research team was flexible with time and meeting families in spaces that were accessible and in the community that was most impacted.

Initial Findings: Since data collection is still ongoing, the findings presented here are preliminary.

All the families interviewed represented born and raised Buffalonians and thus, they had lifelong experiences and were generally ambivalent about winter weather. Several parents reflected on their roles as fathers, mothers, community members, and community leaders.

Families focused on their discomfort with long, gloomy cold weather snaps, a sense of isolation, and low energy with the need for supplements. For youth in the families, snow days and time away from school evoked positive feelings. When parents reflected and compared their overall winter observations, they all overwhelmingly agreed that current winters were “better, and had shifter to be milder, with less snow, and more moderate temperatures.

During the blizzard, families experienced racialized emotions that involved fear, feeling stressed, worry, and sadness. For Black families (parents and children) these experiences reflected a village and care orientation that extended beyond their immediate household. To stay warm after loss of power during the height of the storm, families used generational knowledge and practices that involved using gas stoves and ovens, and multiple layers to stay warm.

Products: Our first presentation of this work will occur during the International Society of the Learning Sciences Annual Meeting in June 2024: Reimagining Justice-Oriented Science Education Through Disaster Memories: Evidence from the Buffalo Blizzard of 2022. Presenters: Wonyong Park, Noemi Waight, Christopher St. Vil, Monica Miles, and Fatemeh Mozaffari.

Developing an Early Mathematics Intervention for Children with Disabilities in the Home Learning Environment

PI: Gena Nelson

STEM Discipline: Mathematics

Grade Levels: Pre-K

Project Description: Young children spend a significant amount of their time in informal learning environments such as the home, libraries, museums, etc., making informal learning environments an optimal space for early mathematics learning and intervention. A recent meta-analysis reported on the overall effectiveness of parent-implemented mathematics interventions, in which the authors also reported that children with disabilities have not been well-represented in the home-based mathematics intervention literature (Nelson et al., 2024). Parents and families play a critical role in young children’s opportunities to learn about mathematics. Thus, including and representing families with children with disabilities is a critical next step for early mathematics home-based intervention research. The ultimate goal of this project is to make home-based mathematics activities—including math storybooks, number games, and everyday routines—accessible for children of all abilities. To do this, our research team is partnering with families to provide feedback on our research process and the home-based mathematics materials that we are developing. Each parent who we are partnering with is a parent of a child with an identified disability. Parents and children will engage in an iterative process in which they will use various home-based mathematics activities, identify barriers and strengths of the materials, and provide feedback and suggestions to the research team about how to adapt the materials for children of various abilities and learning needs. Throughout this project, we are gathering rich quantitative and qualitative data from families about their experiences to inform each stage of intervention development.

What advice would you give to other projects that are considering a family engagement component to their work? And what factors do you think most contribute to successful relationships with families?: Two of the most important factors that have contributed to developing successful relationships with families on this project include (a) engaging families early on in the research project; and (b) engaging other stakeholders who commonly work with families. Based on our experiences on this project so far, we have the following recommendations for other researchers.

Engage Families Early. Many projects may engage with families to provide feedback on materials, such as the curriculum materials that are used directly with children and families. However, we engaged families earlier so that we could gather feedback on our researcher materials, too. In addition to working with families as research participants in our iterative curriculum development process, we first engaged other parents to act as consultants on our project. The parent consultants provided feedback on our email templates to family participants, parent consent forms, data collection protocols, and parent training materials. Rather than assume all of our materials that we intended to use with families were family-friendly, we asked parent consultants to review all of the research protocols and materials to ensure our family participants had a positive experience. We recommend engaging parent consultants in the earliest stages of the project to ensure the project is set up for success from the beginning.

Engage Other Stakeholders. Similar to engaging parent consultants, we also established relationships with other early childhood stakeholders to provide input on our recruitment procedures and materials and research protocols. We worked with classroom teachers, early childhood directors, and other experts in early childhood education to review all of our research materials. From both of these processes, we gathered meaningful and helpful feedback to refine several of our materials before we used them. We recommend establishing a network of stakeholders with expertise across many areas of working with families to provide insight on your materials, including any materials used for research purposes.

Products: Cited in the project description, this publication was under a related, previous NSF Grant (#2000292) Investigating Effective Methods that Adults Use to Improve Children's Math Achievement in Informal Learning Environments: A Meta-Analysis

- Nelson, G., Carter, H., Boedeker, P., Knowles, E., Eames, J., & Buckmiller, C. (2024). A meta-analysis and quality review of mathematics interventions conducted in informal learning environments with caregivers and children. Review of Educational Research, 94(1), 112-152. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543231156182

Integrating Science with Mathematics and Engineering: Linking Home and School Learning for All Young Learners

PI: Ximena Dominguez | Co-PIs: Jillian Orr, Regan Vidiksis

STEM Disciplines: Science, Math, Engineering

Grade Levels: PreK

Project Description: This collaborative project brought together educators, families, researchers, and curriculum and software developers to engage in an inclusive co-design process to create and evaluate resources to promote early STEM across school and home. The effort extended findings from a prior NSF project that involved co-designing and evaluating the promise of a preschool science curricula by: (1) integrating engineering and mathematics with science, (2) creating resources that meaningfully connected home and school learning, and (3) developing resources that address the needs and strengths of Latinx families. Educators and families participated in a series of co-design meetings to brainstorm activities and resources centering children’s experiences and families’ funds of knowledge. For instance, when discussing ideas for the Plants unit, many families expressed that growing plants resonated with them. As they shared about their challenges related to supporting and protecting the plants, they talked about needing trellises to support the plants and using different materials to protect the plants from animals. This idea ultimately served as inspiration for a science and engineering activity and the Berry Garden digital app. The pilot activities were iteratively tested during formative research activities in preschool classrooms and families’ homes. With a new set of educators and families, our team then conducted an experimental field study to examine program implementation in their classrooms and homes and effects on children’s science learning.

What impacts or benefits are you seeing related to family engagement?: By co-designing with families and centering young children’s interests, everyday experiences and community, the team was able to develop science activities that resonated with families. Families were not found to implement the program as intended, but also expressed increased interest in STEM activities, often asking where they could locate more STEM resources. Teachers found the connections between home and school learning to strengthen children’s learning in the classroom.

What advice would you give to other projects that are considering a family engagement component to their work?: Involving families from the start is key. In order for families to feel confident and comfortable working with researchers, teachers and designers, however, it is important to allow time for relationship building and to address dynamics of power and bias.

What supports are you developing and/or providing to families? (why?): Early Science with Nico and NorⓇ, which includes the co-designed activities and resources, is freely and publicly available. The digital family guide available in English and Spanish provides families access to brief, easily adaptable activities related to plants, ramps and shadows to do with their children at home or out in their communities. The final version of the family guide reflects ideas, suggestions and feedback from families from diverse cultural and linguistic backgrounds.

Initial Findings: What we learned when families tested the activities in their homes:

- Children who engaged in the program at home and school made significantly more improvement in science learning, relative to children who implemented at school only.

- Parents/caregivers reported that activities were fun, promoted science learning and meaningfully connected to everyday experiences.

- Parents/caregivers used the digital Family Guide to engage in activities and often modified in ways to best reflect their routines or were inspired to create new activities based on their family’s interests.

Products:

- Early Science with Nico and NorⓇ Family Science Fun: https://first8studios.org/nicoandnor/family/en/

- Integrating Science, Mathematics, and Engineering: Linking Home and School Learning for Young Learners: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12265/180

- Co-Designing Playful Preschool STEM Activities for Everyday Life blog post: https://digitalpromise.org/2023/05/01/co-designing-playful-preschool-stem-activities-for-everyday-life/

- Early Science with Nico and NorⓇ Family Flyer: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12265/179

- NSF STEM for All Video Showcase 2022: https://multiplex.videohall.com/presentations/2624/3738.html

- Kamdar. D., Leones, T., Vidiksis, R., & Dominguez, X. (accepted). Shining Light on Preschool Science Investigations: Exploring Shadows and Strengthening Visual Spatial Skills. Science and Children. https://doi.org/10.1080/00368148.2024.2340805

- Dominguez, X., & Stephens, A. (2022). Supporting Meaningful and Equitable Early Learning Through Science and Engineering. In Handbook of Research on Innovative Approaches to Early Childhood Development and School Readiness (pp. 452-467). IGI Global.

Parents, Teachers, and Multilingual Children Collaborating on Mathematics Together (Collaborative Research)

PIs: Marta Civil, Rachel Pinnow, and Beatriz Quintos Alonso

STEM Discipline: Mathematics

Grade Levels: 2-5

Project Description: The goal of Together Juntos Math, a 4-year project, is to develop and research an innovative mathematical partnership that engages teachers, parents, and multilingual children in grades 2-5, from schools in underserved communities in three different regions of the United States. We use two complementary approaches—positioning theory and funds of knowledge–to develop a partnership model aimed at advancing equity in mathematics education. Using Design-based Implementation Research (DBIR) we led iterative cycles of inquiry to develop, implement and refine the model, and to study outcomes in diverse settings.

The goals of this mathematical partnership were to : 1) reorganize spaces and roles to transform school-home power differentials around mathematics learning; 2) leverage children’s and families’ knowledge and expertise as a resource in teaching and learning mathematics with a focus on problem-solving; and 3) build teacher and parent understanding of the role of positioning in supporting mathematics learning.

Our approach involved study group sessions for teachers, parents, and multilingual children. Their structure varied, including some joint sessions for parents and teachers together; sessions for parents and children together; and separate sessions for parents or for teachers only. Sessions included opportunities for parents and teachers to engage in mathematics activities together with a focus on tasks that foregrounded parents’ / community funds of knowledge. Sessions also included activities for parents and teachers to learn from each other and to engage in discussions about funds of knowledge and participation through the lens of positioning to leverage the assets of multilingual learners.

What impacts or benefits are you seeing related to family engagement?:

- Collaboration with local teachers and families together.

- Leadership development for parents and teachers.

- Leverage funds of knowledge research and positioning theory to understand school community partnerships.

- Teachers engaging parents in their teaching (e.g., co-planning a lesson; providing ideas for lessons).

- Mentoring the next generation of scholars in collaborative approaches to working with communities in mathematics education.

What advice would you give to other projects that are considering a family engagement component to their work?: The main advice we would give is to be candid, reflective, and critical about why you want to have a family engagement component in your work. What is your motivation? For us, one important reason is to learn with and from the families. Families have valuable knowledge and experiences that are often not acknowledged in schools. This belief in the significance of families’ contributions is at the center of the activities we plan. In our work we use open-ended activities that draw on participants’ funds of knowledge as a way to promote more equitable participation between caregivers and teachers. We are very intentional in our facilitation to support participants’ learning from each other’s strengths and experiences and to make sure that caregivers feel comfortable to share their expertise. Key to developing a comfortable environment is the deliberate use of caregivers’ languages, establishing strong relationships, and providing translation as needed.

What challenges have you experienced related to family recruitment and engagement and what strategies have you identified to address them?: Family recruitment can be challenging. Working closely with community members who have established rapport and trust with families has helped us in our recruitment efforts.

What factors do you think most contribute to successful relationships with families?: The key factor is rapport building; this involves listening to the families, learning from them, validating and using their language(s), spending time with them, as one mother once described referring to one of us “She would never try to make us feel that she knew and we didn’t; she was always there working with us so we never felt her having an advantage knowing more than us. She was with us.” Be with them to authentically build reciprocal relationships. Historical and ongoing practices within the educational system, especially in mathematics, have often involved top-down approaches to engaging families. This work requires working towards addressing and repairing the harm caused by these practices. Positioning of multilingual children and community members from historically resilient communities as experts has the potential to start a shift to be partners in education.

Initial Findings:

- Teachers in our project shared overall positive beliefs about the use of native language for instruction and the importance of utilizing pedagogical strategies that are responsive to multilingual learners’ needs. Less positive beliefs were associated with the specific modifications needed for multilingual students. In other words, these results indicate that teachers embrace an equality and not an equity approach to teaching in mathematics classrooms.

- An analysis of classroom observations examined how multilingual learners (MLs) are positioned (e.g., different instructional moves/discourse moves, positioning productively/unproductively as competent/encouraged to participate) across the math lessons. We found divergent approaches by teachers. For instance, some teachers tightly controlled classroom discourse (positioning students as suppliers of answers in whole group discussion, offering closed questions that elicit brief responses from individual students, or choral response from the class). However, other teachers provided a participatory classroom where students were allowed to speak more frequently and felt comfortable as active agents in the classroom. As with prior analyses, we found that when the teacher released control and allowed students to lead the discussion, there were more opportunities for extended discourse and mathematical input by students.

- Findings from the case of a mother and her young daughter working on a problem-solving task, underscore the mother’s use of storytelling to keep her daughter engaged and the use of encouragement for her daughter to pursue her ideas through questions. These interactions between mothers and older children show a collaboration where expertise is shared fluidly between parent and child. Translanguaging was a tool they used to engage and make sense of the problem solving process.

Products:

Project Website: https://sites.google.com/umd.edu/togethermath/home

Publications:

- Quintos, B., Turner, E., Civil, M. (2024). Parents and Teachers Collaborating to Disrupt Asymmetrical Power Positions in Mathematics Education. ZDM Mathematics Education.

Supporting Students' Language, Knowledge, and Culture Through Science

PI: Cory Buxton

STEM Disciplines: General Science with a Forestry emphasis

Grade Levels: 4-12

Project Description: The Supporting Students' Language, Knowledge and Culture Through Science, or LaCuKnoS project, seeks to develop and refine a model of community sustaining science education, bringing teachers, students, families, and researchers together as co-learners. We do this through design-based implementation research focused on three related strands: Language Development for Science Sense Making; Mapping Culture & Community Connections to Science; and Knowledge Building for Informed Decision Making. Family engagement plays a key role in supporting each of these strands. Project implementation primarily occurs in after-school STEM clubs and in school-based family STEAM events. Specifically, our project engages families in STEM learning through three approaches: 1) Model lessons we develop often include community oral history components in which students conduct interviews with family or community members to gather experiential data and then compare this information with other data collected through direct measurements, on topics such as climate change, air quality, and STEM careers; 2) The teacher network we partner with has a longstanding practice of running loosely structured Family Math & Science Nights with the goals of recruiting students to their after-school clubs and showcasing what the clubs have done during the year; 3) The LaCuKnoS team proposed and began implementing more structured Family STEAM Workshops with the goals of promoting more in-depth family conversations about STEM in our lives and communities. Across these approaches, our goal is to support families in understanding that they have many experiences and skills that can enhance their children’s science learning while we also support new interactions between students and parents, and between families and teachers. Creating opportunities for families to learn, do, and talk about science together highlights the roles science already plays in their lives and is central to creating culturally sustaining and asset-oriented science teaching and learning experiences for all students.

What impacts or benefits are you seeing related to family engagement?: Our research on families’ engagement in science co-learning is showing evidence that such experiences positively influence family conversations about science as well as influencing students’ academic and occupational pathways in positive ways. We conduct family interviews at the end of project family nights and family workshops. Parents and children take turns asking each other questions about STEM in their lives, about what they learned in the family events, and about STEM needs and resources in their community. By comparing the family conversations that result from our different family engagement formats, we are noticing ways in which the format of the family engagement influences the nature of subsequent family conversations. For example, when families participate in the less structured family night format, subsequent conversations tend to highlight what was fun and interesting about science but with limited discussion of what was learned or how these ideas relate to needs or resources in their community. In contrast, when families participate in more structured and guided family workshop events, subsequent conversations more explicitly focus on what was learned from the science activities and how these ideas connect with personal interests and with community needs and resources. Our project also gives students periodic surveys about their STEM interests, attitudes, and goals. One finding from the survey data is that students have become increasingly interested in forestry topics, which is an emphasis in our project and is also a strong family and community connection in many parts of our state.

What advice would you give to other projects that are considering a family engagement component to their work?: We have found that most schools have explicit family engagement goals but that the actions and activities they create to support family engagement are rarely well aligned with those goals. For example, school plans for family engagement usually highlight one-directional dissemination of information from the school to the home without sufficient attention to what teachers and administrators can learn from their families. Projects that are considering family engagement components may wish to facilitate conversations with school partners about this question of alignment and how the project might help its school partners strengthen this alignment to better meet their family engagement goals.

What challenges have you experienced related to family recruitment and engagement and what strategies have you identified to address them?: It’s well known from the existing research on family engagement that some of the most common challenges involve logistics and issues of trust or care. In terms of logistics, timing, transportation, and childcare are often obstacles for many families that can prevent or limit their engagement. Talking with families and schools about creative options (Saturday meetings, using community settings, providing transportation, creating separate STEM activities for younger siblings, etc. have all proven successful for us) can help organizers recognize areas of flexibility they may not have considered. Providing food during family engagement events is common practice but there are often untapped opportunities for explicit networking and community building activities (within families, across families, and including teachers) that can be tied to those shared meals. In terms of issues of trust and care, even when teachers and families want to strengthen relationships, there can be differences (language, culture, attitudes about school, etc.) that can show up as obstacles. When teachers, parents, and students spend time together doing STEAM activities as co-learners, this provides new opportunities to build mutual trust and care that can strengthen those relationships moving forward.

What factors do you think most contribute to successful relationships with families?: One of the mantras of our project is this, “Everyone has something to teach, and everyone has something to learn.” Nowhere is this more true than in our family engagement events. Parents want to share things about their family history with their children and to share with teachers about skills and interests they see in their children outside of school. Many parents also want to learn about STEM themselves and about community resources. Teachers want to share about their goals for their students so that parents can work as partners in their children’s education. When teachers are invited to bring their own children to such events as well, teachers can learn that their students’ families and their own family may have more in common than they realize. Children, of course, are the centerpiece around which all of this revolves. Most children enjoy learning and creating things with their families and with their teachers and love sharing their interests in these co-design spaces.

What supports are you developing and/or providing to families? (why?): The model lessons we send home with students include oral history components that give families a chance to share family and community history and experiences with their children in a way that feeds this information back to teachers. The loosely structured Family Math & Science Nights that are well established in the communities we work in give students a chance to share what they have been doing in their STEM clubs with their families. These events also give parents a chance to talk informally and strengthen relationships with teachers and with other parents who may have related goals for their children. The more structured Family STEAM Workshops we facilitate promote more in-depth conversations within families about STEM in their lives and communities. Finally, the family interviews we facilitate through each of these activity types provide families with opportunities to engage together in science talk that can build communication skills, strengthen community connections, and deepen knowledge about how science and technology can be applied in their daily lives.

Products:

- QR Code with access to our model lessons:

- Family interview protocol - LaCuKnoS Family Interview Protocol 2024.docx

- Handout from AERA roundtable - Handout for AERA 2024 family engagement roundtable final.docx

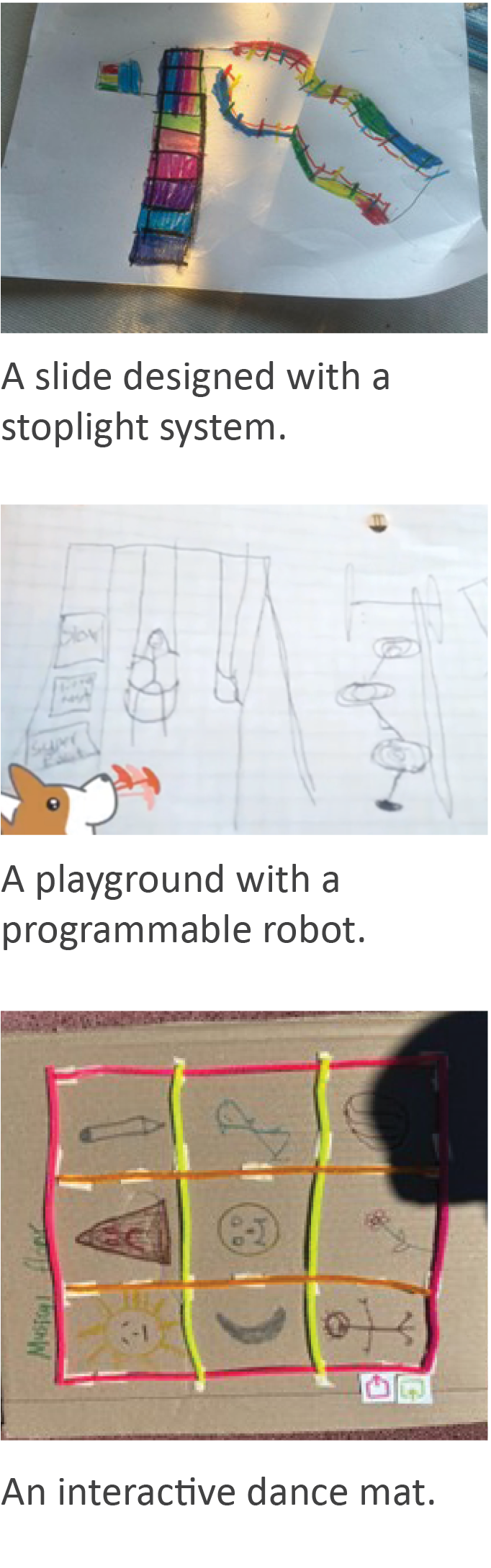

The Smart Playground: Computational Thinking Through Robotics in Early Childhood (Collaborative Research)

PIs: Marina Bers, Andres Bustamante, Chris Rogers, and June Ahn

STEM Disciplines: K

Grade Levels: Computational Thinking, Computer Science

Project Description: Technology and computing are increasingly central in the lives of children and building foundational skills in Computational Thinking in the early years is a national imperative. Young children learn best through play and in educational environments that sustain their cultural practices and identities. This project will co-create and study, an outdoor robotic-augmented playground called the “Smart Playground” and a corresponding series of classroom lessons. The Smart Playground will be co-designed with Latine families and educators to engage young children (Kindergarten) in developing Computational Thinking skills and learning about robotics in a physical environment using a culturally sustaining approach. The project will retrofit existing playgrounds in a low-income, predominantly Latine school district with circuit boards, sensors, and actuators. These boards will allow young children to program their playground to interact with them in different ways. By programming interactive games that involve the playground structures, children will learn foundational Computational Thinking skills, such as modularity (breaking down actions into smaller components), debugging (working to resolve an issue in programmed instructions), control structures (conditional or looped events that result in different event pathways), and algorithms (sequenced patterns of behaviors). Further, through co-designing with Latine families and educators the project will center the technology and activities in families’ routines, values, and cultural funds of knowledge. This proposal will contribute to the emerging field of robotics in early childhood education by addressing the lack of new technologies and approaches for teaching with and about technology in a developmentally appropriate and culturally sustaining way.

What impacts or benefits are you seeing related to family engagement?: We have held four 2-hour co-design sessions with ~15 Latine families from our community partner the Santa Ana Early Learning Initiative (SAELI) around developing initial prototypes for the Smart Playground. These sessions have surfaced cultural values, practices, and family playground routines that are inspiring prototype ideation and iteration. Families also directly ideated and play-tested playground prototypes. Grounding project prototypes in families lived experiences should lead to playground interactions that build on children’s cultural strengths, reinforce family values, and build foundational computational thinking skills.

What impacts or benefits are you seeing related to family engagement?: We have held four 2-hour co-design sessions with ~15 Latine families from our community partner the Santa Ana Early Learning Initiative (SAELI) around developing initial prototypes for the Smart Playground. These sessions have surfaced cultural values, practices, and family playground routines that are inspiring prototype ideation and iteration. Families also directly ideated and play-tested playground prototypes. Grounding project prototypes in families lived experiences should lead to playground interactions that build on children’s cultural strengths, reinforce family values, and build foundational computational thinking skills.

Our co-design sessions with families have yielded a variety of prototypes, themes, and design goals. Here we provide a few examples to illustrate the children and families’ contributions:

- A slide designed with lights that activate upon use and incorporates a stoplight system that children will program to manage turn-taking. The stoplight system for managing turn-taking on the slide exemplifies the Latino cultural emphasis on being bien educado or well educated, fostering virtues of respecting rules and cooperation as children learn to wait their turn, echoing core principles upheld within many Latino households.

- This playground features a programmable robot that children can set to push swings at their preferred pace. The robot's design is a manifestation of prosocial behaviors — intentional acts meant to help others, reflecting the strong helping tendencies often embodied by Latino children. It emphasizes these behaviors by assisting with swing-pushing to enhance the play experience for all children.

- An interactive dance mat allows children to activate programmable musical sounds by jumping on images that light up. The dance mat, infused with Latino music and cultural imagery, celebrates heritage and nurtures children's identity, fostering intergenerational bonds as elders share stories tied to these elements.

What factors do you think most contribute to successful relationships with families?: We have a long-standing relationship with SAELI (~6 years) that is set on a foundation of trust and mutualism. We engage in specific practices to maintain and strengthen our relationship and center family voices in all of our engagements. For example, all of our meetings are held in Spanish which is the dominant language of our community partners. We also begin every session by sharing a meal together and building personal relationships. We offer families stipends to honor their time and contributions. Lastly, we operate with transparency, sharing back design themes and ideas at each session and demonstrating how families’ contributions are being integrated into project prototypes. These practices communicate respect which is key for authentic partnership.

Young Mathematicians: Expanding an Innovative and Promising Model Across Learning Environments to Promote Preschoolers' Mathematics Knowledge

PI: Jessica Young

STEM Disciplines: Early mathematics: Number and operations, geometry, patterning, spatial representation, measurement, data

Grade Levels: PreK (ages 3-5)

Project Description: The Young Mathematicians (YM) project aims to power up teachers and families of children ages 3- to 7-years-old by developing and implementing materials, resources, and teacher professional learning to promote preschoolers' mathematics knowledge and love of mathematics at home and at school. In collaboration with families and teachers at three Head Start programs, we worked to promote strong school-family partnerships and parent-child communication centered around connecting math at home and math at school. We offered teacher professional learning in family engagement, early mathematics, and mathematics games. During the project, teachers implemented multiple strategies to connect with families and engage them as partners in their children’s mathematics learning.

Using a formative design-based research approach we co-created, tested, and refined high-quality, cognitively challenging, mathematics games to ensure that they are engaging and enjoyable for children, families and teachers. Together, we have created over 55 different games that are easily adapted for different ages of children and different contexts. Each game has a corresponding direction page and three-to-five-minute video that explains in an informal, conversational tone, how-to-play and the mathematics learning and mathematics vocabulary embedded in each game. In order to reach as broad an audience as possible, these resources are freely available on our website, www.ym.edc.org, in English, Spanish, Portuguese, and some in Haitian Creole. Our dissemination plan includes outreach to families through social media channels such as YouTube, Instagram, and Facebook, and webinars and presentations to family-facing organizations such as the National Association of Family, School, and Community Engagement (NAFSCE).

What supports are you developing and/or providing to families? (why?): To support teachers and families to engage in mathematically rich interactions in Head Start classrooms and children’s homes, we co-designed and developed fun, playful, mathematics games aligned with early learning standards in number, geometry, data analysis, and spatial reasoning. Within richly diverse community settings, we investigated how this early mathematics program could be successfully integrated into classrooms and family life using a co-design for learning process.

Initial Findings: Findings highlighted the desire of both teachers and families to have games with supporting materials that were highly illustrative with minimal text, adaptable for children of different ages and skill levels, and inclusive of diverse languages that used an informal voice and everyday language. Families and teachers suggested that the design features should be embedded in the game directions to create educative resources and materials that can be readily adopted and implemented without the need for intensive or ongoing external support. Additionally, findings revealed that families were interested and wanted to learn new mathematics vocabulary within the context of the games, with scaffolded exposure to math concepts. Teachers and families independently suggested including simple video instructions to support implementation. Families and teachers also indicated that online open access to all the games and resources would be helpful for playing and re-playing the games. During interviews and focus groups, families and teachers have reported that the materials are easy to use, easy to adapt, and easy to share with others. They particularly appreciate the clear explanations of how children develop early mathematics concepts and skills.

Ultimately, we’ve learned that when children can bring home and share early math games with their families, with intentionally designed supports, it helps to create a bridge between home and school. Games can offer a common language for teachers and families to have more conversations about children’s math learning, while also allowing families to learn developmentally appropriate ways of engaging young children in mathematics within a fun, playful, and low stress context. We are preparing articles on children’s, teacher’s, and family’s outcomes after participating in the study.

Products:

Website (Educator Facing): https://youngmathematicians.edc.org/

The website hosts 55 early math games with game instruction PDFs and game videos. Each video: 1) is 2-5 minutes long; 2) is professionally translated and narrated in Spanish, Portuguese, and English; 3) provides clear, short instructions for teachers and families on how to play; 4) provides easy to understand information about children’s early mathematics learning. The game instruction PDFs contain: the game goal; materials needed; how to play; related vocabulary; questions to ask; tips for playing; information about what children are learning; the number of players; approximate ages; time to play; and a QR code that leads to the game videos and materials on the YM website.

Audio or Video Products (Educator Facing)

- Reed, K. E. & Young, J. M. (2022, March 30). Math Games: Connecting Home and School Learning. National Association for the Education of Young Children Early Math Interest Forum Bi-Monthly Virtual Meetup.

- Reed, K. E., Young, J. M., Coletti, L. (2021, November 10). It All Adds Up! How Librarians Can Support Math Literacy for Children and Families. Webinar available at https://www.bibliotheca.com/it-all-adds-up-how-librarians-can-support-math-literacy-for-children-and-families/

- Young, J., Reed, K., Clements, L., Fitzgibbons, T. & Penney, N. (2021, May). Young Mathematicians: Transforming Preschool Learning Environments. 2021 STEM for All Video Showcase : Covid, Equity & Social Justice. Public Choice Award. https://stemforall2021.videohall.com/presentations/2154

Published Instructional Materials (Educator Facing)

- Young, J. M., Reed, K., Clements, L., Schifter, D., Spencer, D. B., Goldenberg, E. P., Thompson, S. & Coletti, L. (2023). Pattern and Sorting Games: Kit Guide. New Path Learning.

- Reed, K., Young, J. M., Clements, L., Schifter, D., Spencer, D. B., Goldenberg, E. P., Thompson, S. & Coletti, L. (2023). Dot Card Games: Kit Guide. New Path Learning.

- Young, J. M., Reed, K., Clements, L., Schifter, D., Spencer, D. B., Goldenberg, E. P., Thompson, S. & Coletti, L. (2023). Games with Cards and Dice: Kit Guide. New Path Learning.

- Reed, K., Young, J. M., Clements, L., Schifter, D., Spencer, D. B., Goldenberg, E. P., Thompson, S. & Coletti, L. (2023). Games with Fingers and Counters. New Path Learning.

- Young, J. M., Reed, K., Clements, L., Schifter, D., Spencer, D. B., Goldenberg, E. P., Thompson, S. & Coletti, L. (2023). Shape Cards: Kit Guide. New Path Learning.

- Reed, K., Young, J. M., Clements, L., Schifter, D., Spencer, D. B., Goldenberg, E. P., Thompson, S. & Coletti, L. (2023). Movement Games: Kit Guide. New Path Learning.

- Reed, K., Young, J. M., Clements, L., Schifter, D., Spencer, D. B., Goldenberg, E. P., Thompson, S. & Coletti, L. (2023). Shape Games and Puzzles: Kit Guide. New Path Learning.

Book Chapters (Educator facing)

- Young J.M., Reed K. (2023). It all adds up: Connecting home, school, and communities through family math. In H. Şenol (Ed.), Recent Perspectives on Preschool Education and Care. London, England: InTech Open. ISBN 978-1-83769-247-7; DOI: 10.5772/intechopen.112714.

- Young, J.M, & Reed, K.E. (2020). Advancing Equity: Playful ways to extend math learning at home. In Friedman, S. & Mwenelupembe, A (Eds.), Each and Every Child: Teaching Preschool with an Equity Lens (119-123). Washington, DC: NAEYC.

Journals or Juried Conference Papers

- Reed, K. & Young, J. M. (2022). Young Mathematicians: A Successful model of a Family Math Community. Connected Science Learning: NSTA. https://www.nsta.org/connected-science-learning/connected-science-learning-july-august-2022/young-mathematicians

Other Conference Presentations / Papers (Educator Facing):

- Young, J.M., Reed, K., Considine, L.M. & Thompson, S. (April 12, 2024). Preschool math: adding families to the equation counts! National Council for Teachers of Mathematics (NCTM) 2024 Virtual Conference. Live virtual presentation.

- Young, J.M. & Reed, K. & Vanee Hall, L. (April 9, 2024). Play with Me! How games and playtime can help your child learn math. National Center for Family Math at NAFSCE. Webinar.

- Young, J.M. & Reed, K. (March 1, 2024). First 10 and Young Mathematicians: Using math games to promote equity and culturally sustaining family engagement in early childhood. First 10 National Network Meeting. Live virtual presentation.

- Reed, K. & Young, J.M. (February 28, 2024). How math games can promote equity and culturally responsive family engagement. 2024 Virtual Early Learning Conference. TFEC: Early Education Initiative. Recorded webinar.

- Reed, K., Thompson, S., & Young, J. (2023). Adding Family Math to the Equation. Teachers Development Group Leadership Seminar. Portland, OR.

- Reed, K., Thompson, S., & Young, J. (2022). A Family Math Learning Community: Bridging home and school contexts to strengthen mathematics learning. National Council of Supervisors of Mathematics. Anaheim, CA.

- Young, J. M., Reed, K. R., Vietze, E., Pearson, S., & Hope-Sowah, E. (Oct. 2021). Lessons from a family math community partnership. National Conference for Families’ Learning. Virtual Conference presentation.

- Reed, K. E., Young, J. M., Vietze, E., and Shi, J. (Oct. 2021). Implementing a family math learning community: Creating a partnership that bridges home, school, and community. NAFSCE Family Engagement Summit. Virtual Conference presentation.

- Reed, K. E. & Young, J. M. (Sept. 2021). Teachers and families working in partnership to provide all young children with meaningful and relevant mathematics experiences. National Council of Supervisors of Mathematics. Virtual Conference presentation.

- Reed, K., Young, J.M., Grimm, S.B., Khan, T. (2021). Promoting Family Math at Home and in Classrooms. Early Childhood STEM Conference. Virtual.

- Reed, K. E. & Young, J. M (2021). Teachers and Families Working in Partnership to Remove Barriers and Provide All Young Children with Meaningful and Relevant Mathematics Experiences. National Council of Supervisors of Mathematics Conference. Virtual.

- Anastasopoulos, A., Thompson, S., L., Coletti, L., Lin Shi, J., Reed, K.E., Young, J. M. (2020). How can we support families to engage their children in mathematics at home during the Covid-19 crisis?. National Association for the Education of Young Children Professional Leaning Institute. Virtual.

- Young. J. M. (2020). Young Mathematicians: Advancing access and equity through family math community engagement strategies. Family Math Implementation Project Coordinating Committee. Invited Presentation. Virtual.

Conference Presentations / Papers (Research audience):

- Young, J.M, Reed, K, Schifter, D. & Spencer, D. (June, 2023). Games for Young Mathematicians: Promoting mathematics engagement in Head Start preschoolers’ learning environments. National Science Foundation DRK-12 PI meeting. Washington, DC.

- Young, J. M., & Reed, K.E. (2020). Advancing access and equity in early math through family engagement strategies. Boston College Lynch School of Education and Human Development Colloquium Series Inequality, Opportunity, and Child Development. Chestnut Hill, MA.

- Young, J. M., Reed, K.E., Clements, L., & Schifter, D. (2020). Young Mathematicians: Expanding an Innovative and Promising Model Across Learning Environments to Promote Preschoolers’ Mathematics Knowledge. Society for Research on Educational Effectiveness. Virtual.

Additional Projects

We invite you to explore a sample of the other recently awarded and active work that include a family engagement component in the DRK-12 portfolio.

- Developing and Researching K-12 Teacher Leaders Enacting Anti-bias Mathematics Education (PIs: Ruth Heaton, Eva Thanheiser, Cathery Yeh)

- Early Emergence of Socioeconomic Disparities in Mathematical Understanding (PI: Elizabeth Votruba-Drzal)

- Enhancing Early Childhood Educators' Reflective Practice and Content Knowledge to Increase Children's Capacity for Science Talk (PI: Soo-Young Hong)

- Learning in Places: PK-5+ Field-based Science Education Across Schools, Families, and Communities (PIs: Megan Bang, Carrie Tzou)

- Over-Engaged Parenting and Science Achievement in Early Childhood (PI: Julia Leonard)

- Supporting Consequential Learning in Middle School STEM through Rightful Familial Presence (PI: Angela Calabrese Barton)

- The Developmental Emergence and Consequences of Spatial and Math Gender Stereotypes (PI: Sara Cordes)

- The Effects of Family Engagement on STEM Learning and Motivation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PI: Tyler Smith)

- The Impact of COVID on Childrens' Well-being in 2022: Continued Evidence from the Understanding America Study (PI: Anna Saavedra)

Related Resources

- DRK-12 Publications:

- Family-school partnerships in a context of urgent engagement: Rethinking models, measurement, and meaningfulness

This commentary highlights key themes across the five chapters of this volume, as well as offers specific recommendations concerning future directions for inquiry on the issue of family–school connections… - Using Interviews to Identify the Resources of Multilingual High School Students

The resources that multilingual students bring to school mathematics are often ignored. During a teacher-researcher collaborative project focused on creating more equitable learning environments in high school math classrooms… - Family Science Activities

Each short video provides ideas for family science activities for preschool-grade 3 students that reinforce NGSS 3D learning.… - Early Math with Gracie & Friends

Play nine math learning apps and dozens of hands-on activities at home or in the classroom. A digital Teacher's Guide supports use in the classroom, and a digital Family Fun Guide provides activities to do at home.… - Scientific Inquiry for Young Children: Linking Teacher Professional Development and Family Engagement to Improve Student Achievement

These presentation slides describe the NURTURES program which combines teacher professional development, classroom extension activities (family packs) and community sci-FUN events and WGTE learning segments… - Families’ Capacity to Engage in Science Inquiry at Home Through Structured Activities

The role that caregivers can play in their child’s science education is often overlooked within science education research. Few studies have focused on the capacity and abilities of caregivers to guide science activities.…

- Family-school partnerships in a context of urgent engagement: Rethinking models, measurement, and meaningfulness

- Other Related Spotlights:

- Citizen Science in K-12 STEM Education (2019)

- Culturally Responsive STEM Education (2022)

- Early Childhood Education (2020)

- English Language Learners (2020)

- Inclusive Mathematics Education (2023)

- Informal & Formal STEM Education (2021)